Snapping turtles are all too often victims of intentional or simply careless vehicle strikes. Those of us who care about turtles are often quick to criticize the driver and assume they are at fault. But doing so may be misguided. There’s one particular type of snapper injury that bears the hallmark of someone who tried to avoid hitting the turtle, and the male that arrived yesterday is a good example.

In April and May, when most other turtle species are just beginning to venture beyond their hibernacula, snappers and painted turtles are already on the move, crossing roads. They’re mostly males—nesting season doesn’t begin until late May or early June—and out looking for mates or new digs. They’re not moving fast, even by turtle standards, because it’s still cool outside; as cold-blooded creatures, their energy levels are dictated by the temperature of their environment. So, when one of these fellows decides to cross a particularly busy section of road where it’s nearly impossible to pull over or swerve around him, most well-intentioned drivers do what seems like the only alternative: they drive over the turtle, straddling it with their tires, hoping it will pass under their car unscathed.

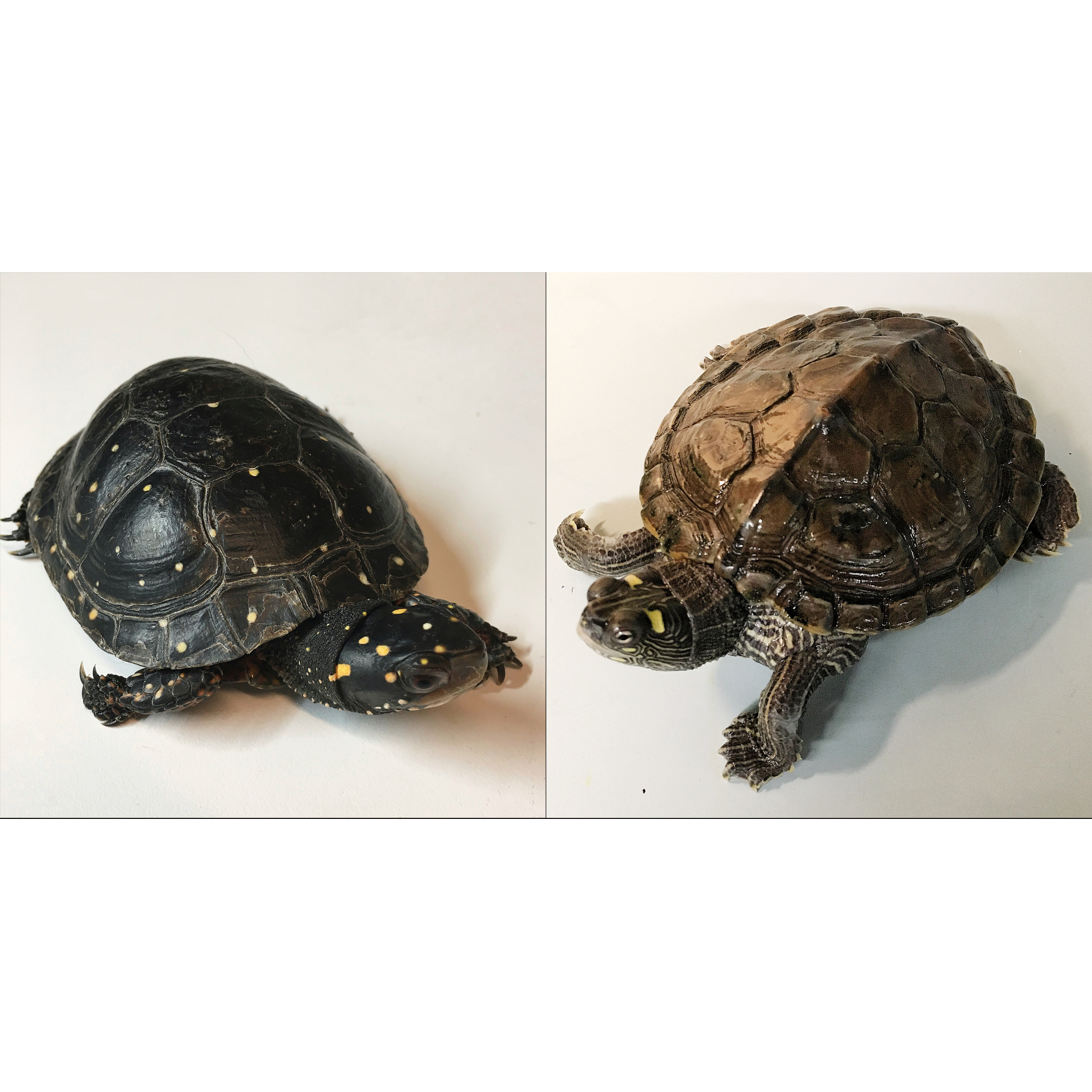

Unfortunately, most auto undercarriages are too low to avoid contact with a snapper that’s walking up on all fours, usually with his head held high. The result is a scraped or even sheared off shell and all kinds of damage to the face and beak.

When a car shears the top off a snapper shell, the wound looks horrific. There’s a lot of blood, not only because of the thick muscle tissue there, but also all the blood vessels running through the shell, which is bone. Rather than the linear fractures to the shell characteristic of being run over by a vehicle, this kind of injury (known as an avulsion) is more a shredding of bone, muscle and connective tissue, and can even result in actual holes into the body cavity, exposing internal organs.

Miraculously, however, the spine is rarely affected, despite its location along the midline of the carapace, and with supportive care the turtle will eventually grow new bone to replace the damaged areas of its shell. In fact, avulsions are usually the worst looking but least catastrophic of all snapping turtle injuries caused by motor vehicles.

Fixing a snapper face, however, is another thing altogether…and not for the obvious reason! A snapping turtle with facial trauma is generally a pretty docile creature. Our new patient was totally cooperative as I pulled clot after clot out of his mouth and repositioned his broken beak pieces last night; he even held his mouth open for me. Thankfully his left eye wasn’t a casualty of the orbital fracture around it. But it’s very difficult to get those broken pieces to stay in place, both because it’s hard to get anything to remain adhered to the keratin beak or the rough skin around the face, and because, of course, the mouth moves a lot. Snappers in the wild, though, are often found with badly deformed faces and mouths and doing just fine. They heal up, one way or the other, and since they swallow using suction in water, as long as they can get food into their mouths, they manage.

If you come across a snapper with this kind of injury, don’t immediately curse the driver that caused it. They were probably doing the only thing possible to save the turtle at the time, and the victim stands a very good chance at full recovery…and release.